The costs of converting a farm to specialty coffee.

An example from David Batres, and Finca Batres.

By Peter Jones.

—

This article has come out of an ongoing conversation that Peter and David Batres of Finca Batres, in Guatemala, have been having for the past couple of months. We are eternally grateful to David for having this conversation, being fully transparent in terms of the cost and logistics behind converting part of his farm from good coffee to exotic/specialty coffee, and for simply tolerating all the questions Peter asked repeatedly. The conversation started in part because we (Idle Hands) wanted to make sure we paid David enough for his coffee, as well as to explore ways we could collaborate in the future to ensure David is successful in his coffee farming journey.

Every farm, country, coffee varietal, etc. changes these numbers slightly up or down. The numbers presented here are particular to David’s farm in Guatemala and the meticulous way he processes his coffees. However, they shine a powerful light on just how much it costs to run a coffee farm and how important it is to work collaboratively with the people you buy coffee from so that everyone gets a fair share of the profits.

Finca Batres is located high up in the mountains right on the border between the Santa Rosa and Jutiapa departments, in what is known as the Sur Oriente area, in the Eastern Highlands of Guatemala. David Batres, along with his wife, own the small 2.5 hectare farm, which is currently producing Tekisic, ANACAFE 14, and other varietals. Although this area of Guatemala receives enough rain to grow coffee, it is less reliable than other areas, and with climate change, rainfall has fluctuated dramatically. As a result, along with other market variables, David is looking for ways to boost the farm’s productivity and income. Although his coffees already regularly score between 86-88 points, he is keenly aware that certain varietals of coffee (sometimes referred to as “exotics” and for the sake of this article, we’ll refer to them as such here) command a higher price in the world market even if they have the same cup score as his current coffees. Therefore, he wants to convert part of his farm from it’s current varietals to one(s) that will command a higher price, such as Gesha, Sidra, Pacamara, and Shakiso.

LAND

A manzana is a unit of area used in many Central American countries including Guatemala and was originally defined as 10,000 square varas in Spanish customary units. One manzana is roughly equivalent to 7,056 square meters, or 1.7 acres. For the discussion here, David is wanting to convert one manzana (about 1/3 of his farm) from more traditional varietals to “exotics” (1). The rest of the farm will continue to produce what is already growing to help finance and keep some modicum of cash flow.

SEEDS

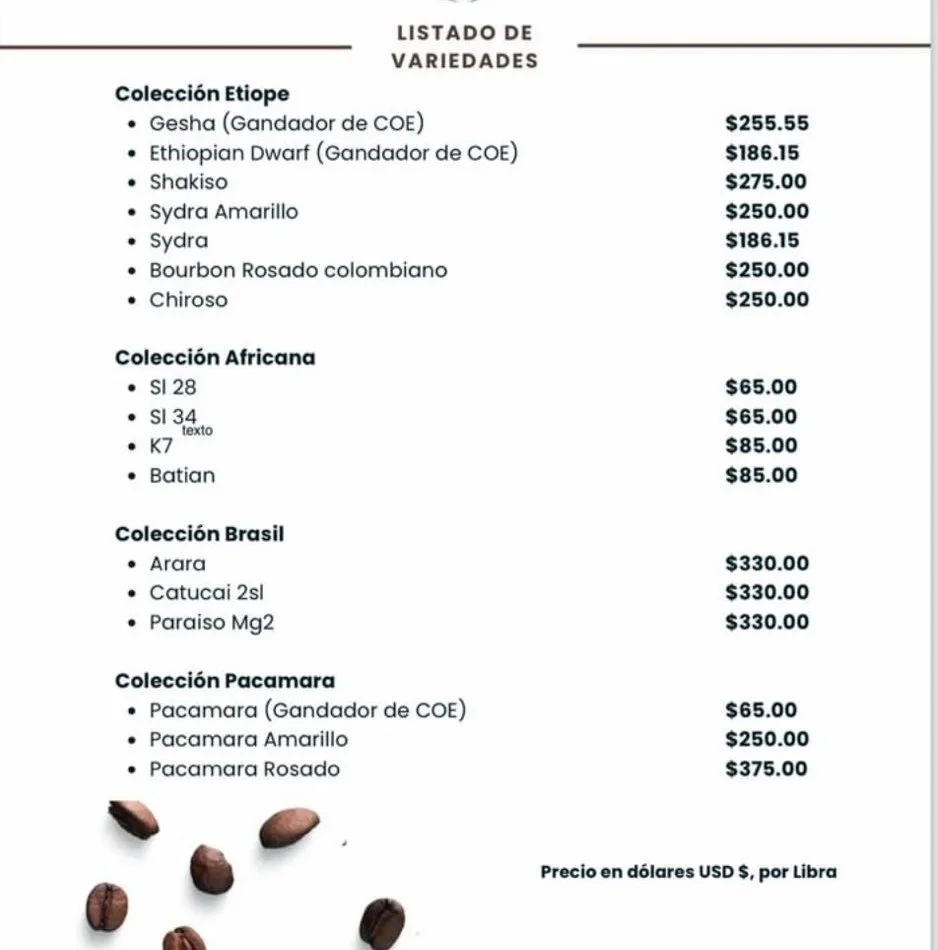

Now that we have the basic unit of measurement for the land, we need to talk about the coffee plants themselves. Many factors go into how many coffee plants can grow on one manzana – the varietal (how tall it is, how bushy it is), the soil type, slope angle and aspect, sun exposure, and so forth, as well as the goals of the farmer (whether they want exotics like Gesha, or are focused on selling cherry where ANACAFE 14 would suffice). All those factors determine how many baby coffee plants can grow on one manzana of land – in the case here it is about 3,535 because David is interested in planting exotics. The current going rate for exotic seeds in Guatemala is shown in the image below, with one pound of seeds equaling about 700-750 plants. That means that if David wants to convert his one manzana from ANACAFE 14 or some other varietal and plant Pacamara or Gesha, he will need to buy at least 5 pounds of seeds.

Seems straightforward, but we have only started the journey, more investment and labor will be needed before David can even start to think about his first harvest. You can’t just plant coffee seeds and hope that they grow up to be big, high yielding coffee bushes. Somehow you need to get the seeds to germinate and sprout, growing into baby coffee bushes about 2-3 nodes high. If you don’t have the ability to do that, which many farmers don’t, you need to pay a nursery. In Guatemala that service is currently running about $200-$300 per pound, which means it costs about $1,000-$1,500 for one manzana worth of germinated and ready to plant baby coffee bushes.

PLANTING

Okay, so we’ve figured out pricing for the coffee seeds, then germinating and getting those seeds to the baby plant stage, but what about prepping the land and planting all those baby coffee plants on the farm? A lot of work needs to be done to prep the land before you can just plant coffee – the land needs to be cleaned (all the low-lying plants need to be cleared), holes for every coffee plant need to be dug (it costs about 1.5 quetzal for one hole, so around $400 per manzana), trucking the baby coffee bushes to the farm from the germination nursery, and so on. All told, about another $1,000-$1,500 is required to get the land ready and the baby coffee bushes planted.

Let’s add all this up to see how much cash David must have just to get baby coffee bushes in the ground. And, this does not account for what comes after.

Seeds 1 pound of seeds = $250. Need 5 pounds of seeds, so the cost for one manzana is roughly $1,250.00

Germination/Nursery Germinating and nursing to baby coffee plant stage for 5 pounds is roughly $1,000-$1,500.00

Land Prep and Initial Planting Getting the land ready and digging the holes for one manzana is roughly $1,000-$1,500.00

So just to get the ball rolling and for coffee plants to be in the ground, David needs to spend between $3,250 - $4,250 to replant one manzana (1.7 acres) of his farm.

TIME; WAITING AND WORKING

Coffee plants are not like bamboo; you need to wait 2-3 years before the first harvest is possible. In the time between planting and first harvest, work still needs to be done – weeding all around each baby coffee bush, pruning the bushes and removing dead limbs, feeding the bushes with nutrients, and other work all needs to take place. All that work requires money, money that must come from sources other than the young coffee bushes you are waiting to grow and eventually harvest.

POTENTIAL

Between 3.3-4.5 pounds of cherry per coffee plant is what David is generally harvesting on his farm, although that number changes depending on the coffee varietal, slope angle, aspect, etc. But for now, let’s go with that. David is very meticulous, and he only uses fully ripe cherries, tossing out anything under 95% ripeness so the numbers we are using below might be a bit tight (i.e., with less precise sorting, one could increase the yield to more than what is presented below). In David’s experience, with very precise sorting and picking, he only gets about 1 pound of green coffee from about 6.5-7.5 pounds of fresh cherry. That means that it takes basically two mature coffee bushes with a solid cherry load to arrive at one pound of green coffee ready to roast. Going back to the one manzana of land David is switching to specialty/exotics, that means potentially if everything works out just right, he can expect to harvest around 13,200-18,000 pounds of coffee cherry, which after processing and milling, will result in 2,030-2,400 pounds of green coffee.

Two thousand pounds of green coffee sounds pretty dang good, but is it really? If he sells the green to a roaster or green trader for $4 per pound, that will get him a nice $8,000-$9,000 paycheck. Sound good? Um, not really. Can you live off $8-9k per year? Say David converts his entire farm, that still only gets him $28,000-32,000 per year at the $4 per pound rate.

MORE HIDDEN COSTS

But wait, we forgot a whole bunch of expenditures – taxes on the land; maintenance and upkeep of the farm equipment, drying beds, pulper, and so on; paying gas and electric bills; paying someone to mill the coffee (sometimes the green trader or roaster takes this cost on, sometimes the farmer does); paying all the workers to help pick, clean, sort, transport, and process the coffee. The list goes on and on. In 2022 FEDECOCAGUA (Federacion de Cooperativas Agricolas de Productores de Café de Guatemala) estimated that it costs about $2,157 dollars a year to keep a one manzana coffee farm going (2). So now factor all that into the above numbers, and that $8-9k per year per manzana number starts to shrink fast.

At this point it is pretty easy to see why David wants to convert part of his farm to specialty/exotics – it’s all in the numbers. However, it is also pretty obvious that the initial outlay of cash is quite big, and the risk quite large, along the lines of $9,721-$10,721 per manzana before the first harvest potentially happens (lots can go wrong between planting and first harvest two years later).

COFFEE FARMING IS HARD

As I have discussed, and as David has graciously shared, coffee farming is hard and full of risk. A lot can happen between deciding to plant baby coffee bushes and reaping one’s first harvest. Drought, forest fires, too much or too little rain, disease (La Roya), and so on can all ruin a farmer’s total crop and investment. The “risk” of farming is really all on the farmer, and the roaster, green trader, and consumer bear little to no risk, nor do they really know all the challenges that went into growing the cup of coffee we all love.

The purpose of this article is not to provide solutions – there is no one size fits all solution – but to bring awareness about the basic financial costs and risks associated with coffee farming, especially at the startup (or renewal) level. Personally, I knew that coffee farming was risky, but had no real perspective until David was willing to share his numbers and story. This article also highlights the need for roasters to support the farmers they buy from – not just by buying green coffee, but also by being honest, transparent, and collaborative. Farming is not just a one-way transaction of commodities; it is a mutually beneficial supply chain where both the farmer and the roaster benefit and grow when both sides are working together.

As climate change and market instability continue to impact coffee farmers, it becomes increasingly important for those on the receiving end of the supply chain to support the people they buy from. Although there is risk involved in roasting and selling coffee, it pales in comparison with the risk farmers have. Next time you enjoy a cup of coffee, remember all the time, money, and risk that an individual farmer took on to make that cup of coffee happen. In a globalized world, we are all connected, and we need to support each other if we want to continue to enjoy the good things in life, from farmer to roaster to consumer.

Notes

In reality, David is converting two manzanas, which is slightly over half of his entire farm. He is planting Gesha and Red Pacamara. To keep the analysis and discussion simple, all numbers in the article reflect only the conversion of one manzana.

Cited in Tay, Karla, Guatemala Coffee Annual. 2022. USAID and GAIN. Report #GT2022-0005. Last retrieved on August 12, 2025 here.